A short tour of the Harpoon Brewhouse in Boston, MA.

(Recorded 27 June 2013)

How Beer is Made

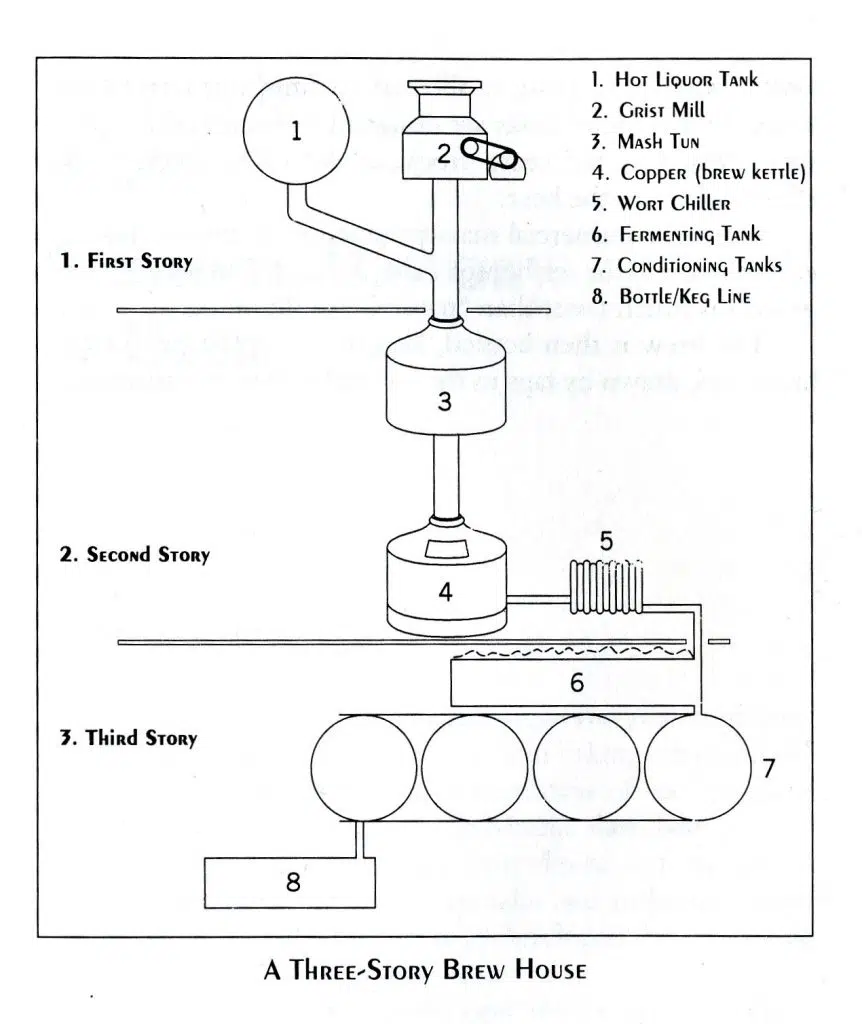

Beer (both Lager and Ale) is made in a Brewhouse. A brewhouse consists of a grist mill, mash tun, brew kettle, chiller, fermenting tanks, conditioning tanks, and a kegging or bottling line.

The traditional brewery (the building containing a brewhouse) is built on at least three levels. This is done to allow gravity to do much of the work of moving the grain, grist, mash, wort, and spent grains.

It was also important that the fermenting and conditioning tanks be in cellars where the temperature was optimum for the fermenting and conditioning of the beer.

THE GRIST MILL

The first step is to crush the grains, to expose the maximum surface area to the water (liquor) in the Mash Tun.

This crushed grain, called grist, is rolled between metal rollers set a specific distance apart. The crushing is done without turning the grain into flour. The grain should be just crushed to allow optimum extraction of the fermentable sugars when hot liquor is added to the grist in the Mash Tun.

A Mash Tun is a large metal container, often copper clad, to efficiently distribute heat to the mash.

THE MASH TUN

The crushed grain (grist) is shoveled into the mash tun where hot liquor (water), heated to approximately 175F, is added. This is the “striking” temperature and is a few degrees higher than the optimum mash temperature of about 150-152F. However, this is the best temperature for the enzymes found naturally in the grain to turn the starches, which make up most of the grain, into maltose (malt sugar) fermented by the yeast later in the process.

The temperature range of the mash creates the optimum environment for the enzyme diastase to convert the starch in the malted barley into sugar and other non-fermentable products. Lower temperatures usually produce more non-fermentables; higher temperatures mean fewer non-fermentable products. These non-fermentables give the finished beer “body” or “mouth-feel.”

The remaining husks and spent grain are allowed to settle to the bottom of the Mash Tun to form a filter of sorts.

After as much of the sweet wort as possible has been drained from the Mash Tun, more hot liquor is sprayed on the husks and spent grain to make sure as much wort as possible is obtained.

THE BREW KETTLE

The wort is next piped into a brew kettle, where the brewing part of the process begins

In the Brew Kettle, the hot wort will be brought to a boil for an hour or so. At the same time, the brewer occasionally adds hops to create a particular flavor profile. After the essential oils from the hops and the proteins are extracted from the wort, the hopped wort is then quickly chilled to around 60F and piped into fermenting tanks.

The Wort Chiller

Almost hidden between the brew kettle and the fermenter is a piece of equipment that is a rectangular construction of thin metal plates with a plastic compact disk holder’s shape and thickness. These are heat transfer plates. They allow the heat to dissipate when the cold water chills the beer to the proper fermentation temperature. The leaves are atop a metal box that has two sets of hoses attached to it. One set of hoses are brick red in color. The other set is black and the thicker of the two sets. The metal box has a few valves and a dial that flashes numbers. The flashing numbers on the chiller tell the brewer the amount of wort that has gone through the chiller.

FERMENTATION TANKS

The fermenting tanks (traditionally open in a clean room) are filled with cool wort. And then, either top-fermenting (ALE) or bottom-fermenting (Lager) yeast is “pitched” (added), and fermentation occurs.

Basically, this is when the yeast metabolizes the sugar in the wort, and the resulting products are ethyl alcohol and carbon dioxide.

Ale can be fermented and conditioned at a higher temperature than Lager. Still, both need cool, stable temperatures to produce the best product.

FINISHING TANKS

And finally, we reach what is called the finishing tanks. Here is where the ale or the beer is stored just before it is served. It goes through a secondary fermentation which allows for carbonation. Natural carbonation gives the beer or ale a creamy flavor and feels in the mouth. There are two ways to carbonate beer.

The first way is to inject carbon dioxide into the beer using compressed carbon dioxide sent through a carbonation stone.

The second way is natural fermentation. This takes place in the finishing tanks. When an additional amount of yeast is added to the beer, so that it may continue fermenting.

Natural carbonation, created by the yeast in the secondary fermentation, results in smaller, more delicate bubbles that add more than just a nuance to the beer.

In most breweries, the finishing tanks are arranged to be close to the bottling and kegging line. In a brewpub, the finishing tanks are situated close to where the consumers will be.

PACKAGING

The brew is then bottled, kegged, or, in the case of pub-breweries, drawn by taps in the bar and served to customers.

HOW EASY IS IT FOR YOU TO MAKE BEER?

Homebrewing beer is a simple matter.

Using either Malt Syrup or Whole Grains, makeup about three gallons of very sweet liquid. (Making a Wort.)

Chill this liquid down by adding two gallons of ice-cold water and pouring this into a five-gallon container (Primary Fermenter).

Add the beer yeast of your choice, loosely cover the fermenter to let the carbon dioxide out, and ferment for a few days.

Siphon this almost beer into another five-gallon fermenting vessel (usually a five-gallon glass water cooler bottle). Allow it to continue fermenting. (Bright Tanks)

Finally, add some malt extract or powdered malt to the fermenter and siphon off the beer into bottles to crown cap. Let these bottles “Lager” for a week or two, crack them open, and enjoy!

Future “Old Growlers” will explore this in detail.