Prehistoric Beer

There is some debate about whether grain was first explicitly cultivated in brewing beer or baking bread. However, there is no doubt that the earliest days of “farming” took place back in 8000 B.C., in what we now call the Middle East, between the Euphrates and Tigris rivers. With the desire to form settlements, rather than remaining nomadic and gathering crops where they grew wild, our ancestors developed the practice of agriculture, and civilization was born.

Even before civilization, the fruits of fermentation were considered gifts from the gods. The discovery of wine was probably a happy accident. Someone left their fruit juice uncovered for a day or two and noticed the foamy froth that began to appear on the surface. Then that brave and lucky person tasted and enjoyed. I must also point out that fruit left unattended in the sun will naturally ferment.

It has been suggested that prehistoric men (or women) discovered beer when they left their bowl of grain mush to sit for a day or so and then sipped the bubbly liquid that rose to the surface. This is a myth. I suggest you try doing it for yourself. I can assure you that the fermenting mix will be undrinkable because even if the grains are boiled in the water as a sort of porridge, microbes of all kinds and other less than desirable beasties will infect the mixture the brew.

It takes treating the grain to turn to sweet sugar when steeped in water and boiled. After that, a relatively controlled fermentation is encouraged by using one batch to begin the next batch. Inbreeding yeast in a way.

Ancient Beers

When beer found its way to Egypt, it was considered a drink for only the royal. This beer was made of grain, ginger, and honey, sweetened with date sugar. To add shelf-life to the beer, the alcohol content was raised by adding more date sugar.

One of the by-products of civilization is the establishment of a complex system of social order. At the top of this social order were the priests.

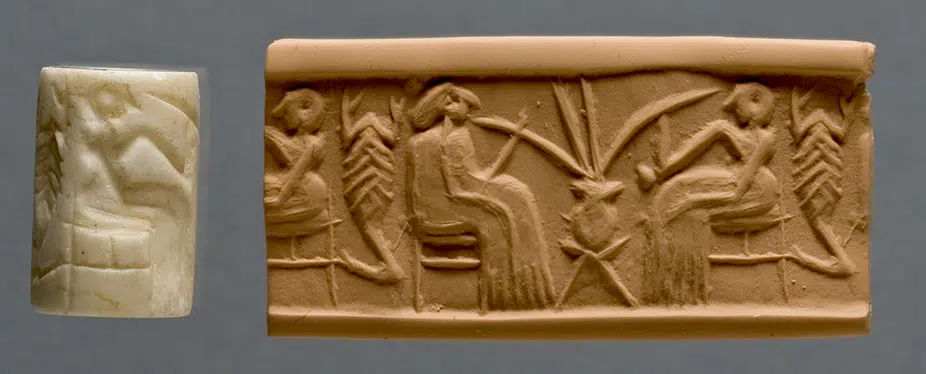

There is little question who got the best of the harvest and the “responsibility” of making sure that wine and beer were made specially to please the gods. Artifacts have been recovered that place beer at the tables of the priests of Ninkasi and Isis.

Becoming the Beverage of The Masses

It was not long before man began to think twice about the idea of reserving beer only for priests or royalty. Beer was soon to become an egalitarian beverage.

Ancient texts indicate that after a hard day’s work, the Sumerians, who lived around 3000 B.C., used straws made from reeds to draw off the fermented liquid from unique beverage containers.

This beer played an essential part in the Sumerian culture. It was consumed by men and women from all social classes. Beer parlors received special mention in the Code of Hammurabi in the eighteenth-century B.C.

Stiff penalties were dealt out to owners who overcharged customers (death by drowning) or failed to notify authorities of criminals in their establishments (execution). In the Sumerian and Akkadian dictionaries being studied today, the word for beer is listed in sections relating to medicine, ritual, and myth.

What did Sumerian Beer taste like?

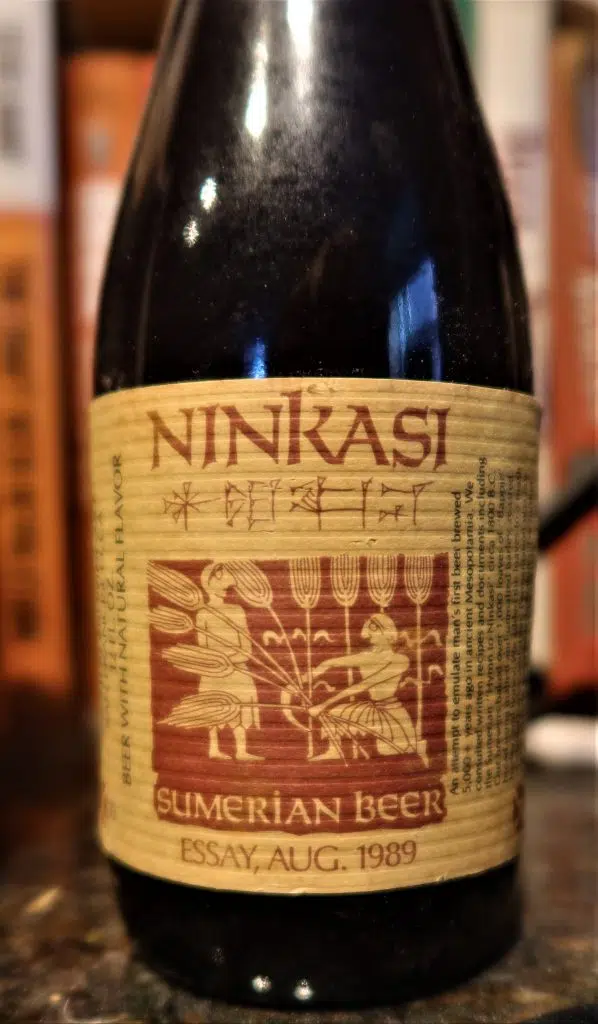

The brewers at the Anchor Brewing Company in San Francisco, CA, were looking for a special event to celebrate the tenth anniversary of their new brewhouse. They saw an article published by the University Museum, the University of Pennsylvania, that described the Beer of the ancient Sumerians. Here was their opportunity to brew, literally, a classic. They accepted the challenge. With the help of historians, they produced a beer that was reported as having “the smoothness and effervescence of champagne and a slight aroma of dates.” Those Sumerians had been on to something good!

The Label reads:

“Symposium Beer – Brewed to celebrate the Institute for Brewing Studies’ 1989 National Microbrewers Conference August 30- September 2, 1989, San Francisco, CA.”

“An attempt to emulate man’s first beer brewed 5,000+ years ago in ancient circa 1800 B.C. Mesopotamia. We consulted written recipes and documents, including the Sumerian “Hymn to Ninkasi” ci 1800 BC. “

“Our brewers baked over 1,00 loaves of “bappir” bread using malted and un-malted barley, roasted barley, and honey.”

“Fermentation was normal at slightly elevated temperatures.”

The European Beer Connection

As civilization spread north, across the Mediterranean, so did beer. The Greeks called the Egyptian beer a “barley wine” and introduced it to the Romans. The latter passed it to other civilizations as they traveled through Europe.

Of course, wine is a lot easier to make than beer. All you do is harvest the grapes, crush the juice from them, let that juice ferment, and drink it. The climate of the Mediterranean was and still is ideal for the growing of grapes. Vines were planted specifically for wine production before Greece had conquered the world.

In Northern Europe, where grain grew in abundance, the preference for beer was drawn by agricultural whim. Where grapes grew in abundance, wine was the beverage of choice. Beer and brewing took hold and flourished where grains were a staple for survival. The Mediterranean area produced wine, and the prosperous breadbasket of Europe became the cradle for the development of what we now know as beer.

Evidence of the early history of brewing in Europe is meager. Still, it reveals that brewing was done by the women as part of maintaining a proper household. The entire family drank fermented beverages made from grain. It was nutritious and was not nearly as dangerous as drinking the contaminated waters found near most towns and villages. (It must be remembered that what we considered standard sanitary practices in the world we live in today were not practiced at that time. Potable water was hard to come by in towns because of less-than-efficient human waste disposal. In rural areas, groundwater was suspect, and spring water was often not near.)

The Growth of Monastic Beers

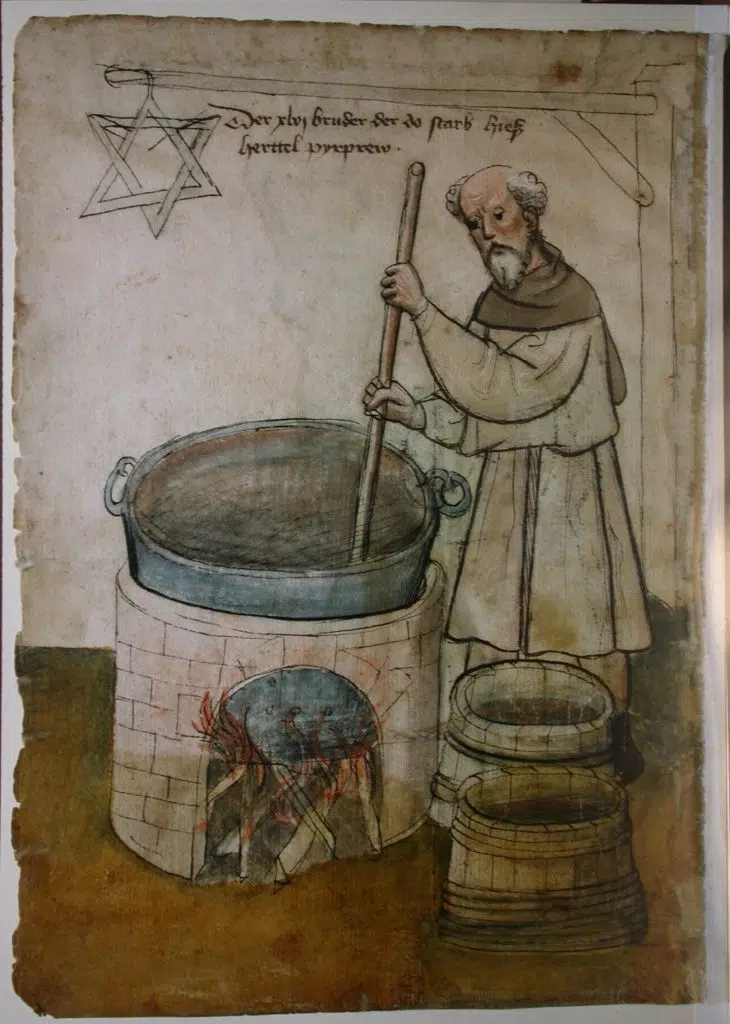

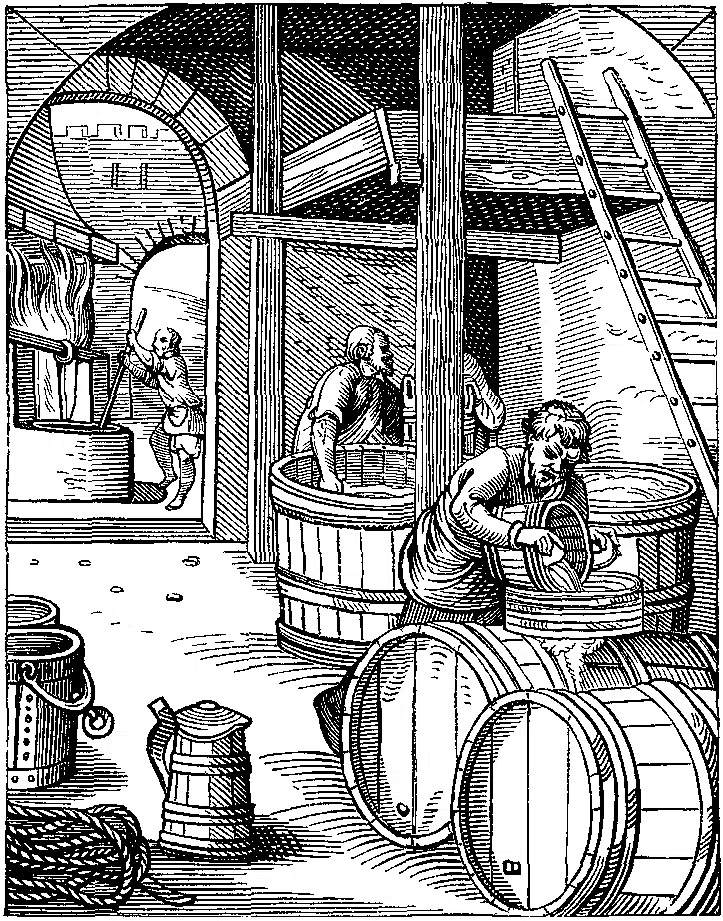

When the end of the classical Roman and Greek civilizations came, and the Holy Roman Empire fell into misuse, the monasteries of Europe were the sole providers of healers, teachers, preachers, and beer. In those times, transportation was by foot, horse, or cart. Travel, at its best, was tedious and dangerous. In this climate, a tradition of hospitality was practiced by the Roman Catholic monasteries. They became way-stations for pilgrims going from one shrine to another or travelers seeking refuge on a long journey. All visitors were offered refreshment, a place to rest, and, of course, a chance to offer prayers and donations for their benefactors. The monks and priests were dedicated to religious pursuits that included humility, poverty, waging wars, nature study, illuminating books, and brewing beer as a subsistence beverage. Some religious groups had such strict dietary restrictions that “liquid bread” was the foundation of the existence of these religious groups. Beer, brewed by the members of the religious community, was the beverage offered to the visitors. Some monasteries also provided beer for trade, sale or barter, with their neighbors.

At that time, herbs and spices were the pharmacies of those who knew how to unlock their secrets.

Hops were used for many things. Among them, a sedative (in pillows) and in shampoo (the oils). As a leather preservative, thanks to resins and oil. The first recorded mention of hops in brewing is in the twelfth-century writings of Hildegarde, the Benedictine nun, abbess of Rupertsberg, near Mainz, Germany. Her writings specifically suggest that hops retard spoilage of beer.

This knowledge was essential to every monastery and brewing guild that wanted to expand their markets. The beer they brewed and shipped needed to last the journey intact. A credit to their brewing skills. Hops made it possible for beer to endure long trips from the brewery where it was brewed to the consumer paying for a superior product and what was available as an everyday beverage. (Sounds familiar to the beer mavens of today!)

In Conclusion:

The identity of the first person to brew beer is lost in antiquity. However, we can be sure they were someone who knew the potential and various uses for grain.

I propose that it was probably a baker who was attempting to find a way to store grain. They tried making cakes out of damp grain for extended storage. They would soon notice what happens to the grain when it begins to germinate. The sweet flavor was substituted for the sweet grape or fruit juice. The boiling of the sweet liquid was probably the result of their attempt to find a way to keep the liquid from tasting terrible from microbic contamination. (A few thousand years later, Louis Pasteur would figure out why the beer went “bad.”)

Once the essential steps of brewing became ritual, the rest is history.

Let’s drink to that!